Using Parallel Magics¶

IPython has a few magics for working with your engines.

This assumes you have started an IPython cluster, either with the notebook interface, or the ipcluster/controller/engine commands.

[1]:

import ipyparallel as ipp

cluster = ipp.Cluster()

cluster.start_cluster_sync(n=4)

rc = cluster.connect_client_sync()

rc.wait_for_engines(4)

dv = rc[:]

rc.ids

Using existing profile dir: '/home/docs/.ipython/profile_default'

Starting 4 engines with <class 'ipyparallel.cluster.launcher.LocalEngineSetLauncher'>

100%|██████████| 4/4 [00:08<00:00, 2.07s/engine]

[1]:

[0, 1, 2, 3]

%px, %%px, %pxresult, pxconfig, and %autopx.Now we can execute code remotely with %px:

[2]:

%px a=5

[3]:

%px print(a)

[stdout:2] 5

[stdout:1] 5

[stdout:3] 5

[stdout:0] 5

[4]:

%px a

Out[0:3]: 5

Out[1:3]: 5

Out[2:3]: 5

Out[3:3]: 5

[5]:

with dv.sync_imports():

import sys

importing sys on engine(s)

[6]:

%px from __future__ import print_function

%px print("ERROR", file=sys.stderr)

[stderr:1] ERROR

[stderr:0] ERROR

[stderr:3] ERROR

[stderr:2] ERROR

You don’t have to wait for results. The %pxconfig magic lets you change the default blocking/targets for the %px magics:

[7]:

%pxconfig --noblock

[8]:

%px import time

%px time.sleep(1)

%px time.time()

[8]:

<AsyncResult: execute>

But you will notice that this didn’t output the result of the last command. For this, we have %pxresult, which displays the output of the latest request:

[9]:

%pxresult

Out[0:8]: 1631278502.24939

Out[1:8]: 1631278502.2469072

Out[2:8]: 1631278502.2612648

Out[3:8]: 1631278502.2637527

Remember, an IPython engine is IPython, so you can do magics remotely as well!

[10]:

%pxconfig --block

%px %matplotlib inline

[stderr:1] WARNING:matplotlib.font_manager:Matplotlib is building the font cache; this may take a moment.

[stderr:2] WARNING:matplotlib.font_manager:Matplotlib is building the font cache; this may take a moment.

[stderr:3] WARNING:matplotlib.font_manager:Matplotlib is building the font cache; this may take a moment.

[stderr:0] WARNING:matplotlib.font_manager:Matplotlib is building the font cache; this may take a moment.

%%px can be used to lower the priority of the engines to improve system performance under heavy CPU load.

[11]:

%%px

import psutil

psutil.Process().nice(20 if psutil.POSIX else psutil.IDLE_PRIORITY_CLASS)

[12]:

%%px

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

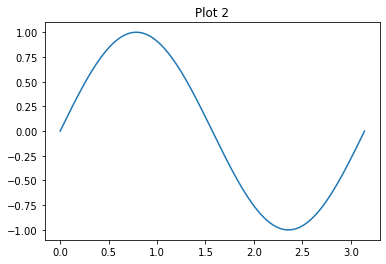

%%px can also be used as a cell magic, for submitting whole blocks. This one acceps --block and --noblock flags to specify the blocking behavior, though the default is unchanged.

[13]:

dv.scatter('id', dv.targets, flatten=True)

dv['stride'] = len(dv)

[14]:

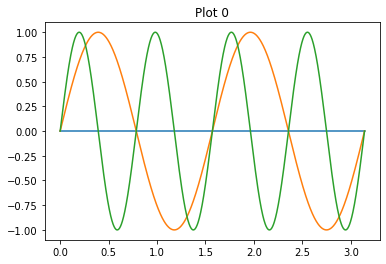

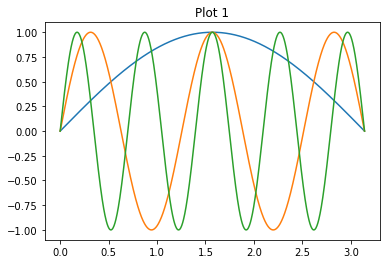

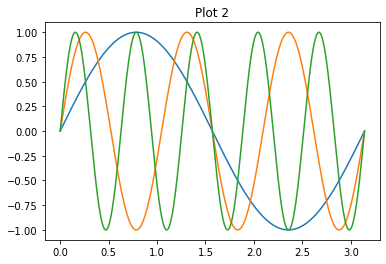

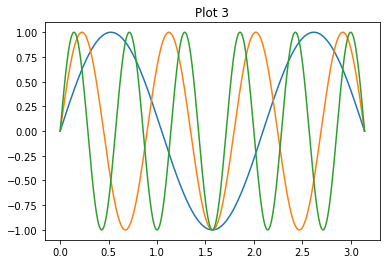

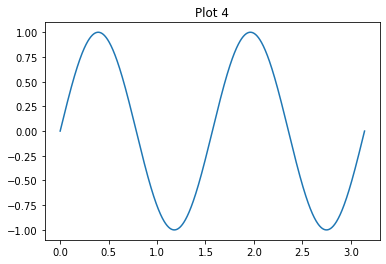

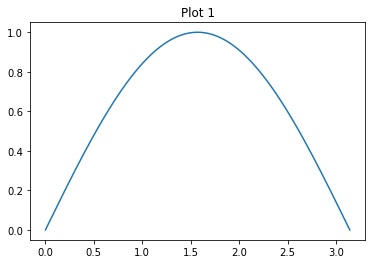

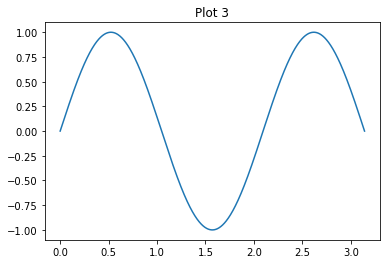

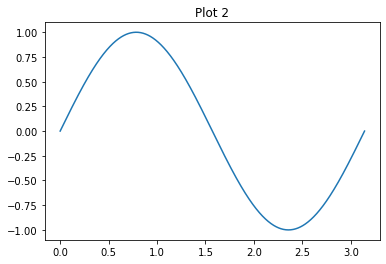

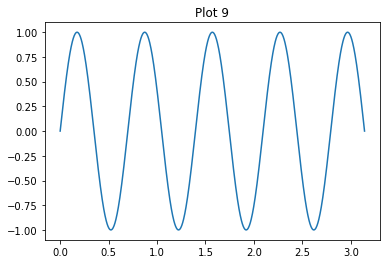

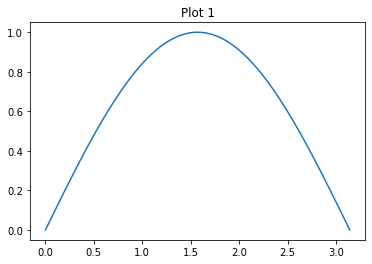

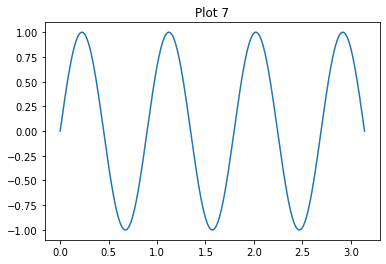

%%px --noblock

x = np.linspace(0,np.pi,1000)

for n in range(id,12, stride):

print(n)

plt.plot(x,np.sin(n*x))

plt.title("Plot %i" % id)

[14]:

<AsyncResult: execute>

[15]:

%pxresult

[stdout:0]

0

4

8

[stdout:1]

1

5

9

[stdout:2]

2

6

10

[stdout:3]

3

7

11

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

[output:3]

Out[0:12]: Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Plot 0')

Out[1:12]: Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Plot 1')

Out[2:12]: Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Plot 2')

Out[3:12]: Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Plot 3')

It also lets you choose some amount of the grouping of the outputs with --group-outputs:

The choices are:

engine- all of an engine’s output is collected togethertype- where stdout of each engine is grouped, etc. (the default)order- same astype, but individual displaypub outputs are interleaved. That is, it will output the first plot from each engine, then the second from each, etc.

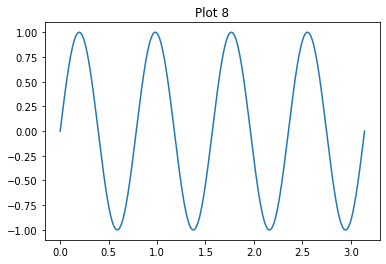

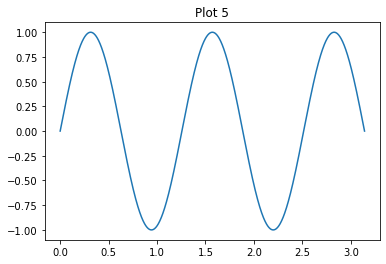

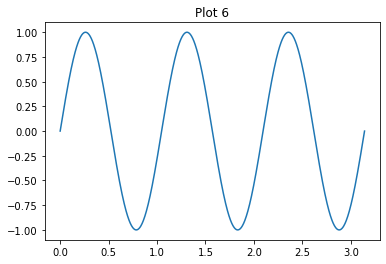

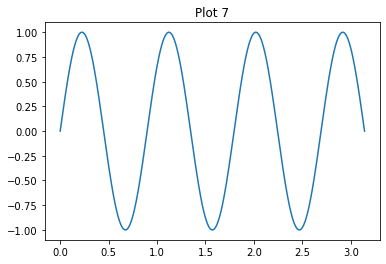

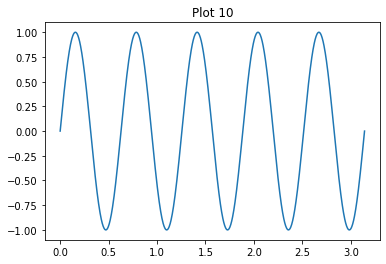

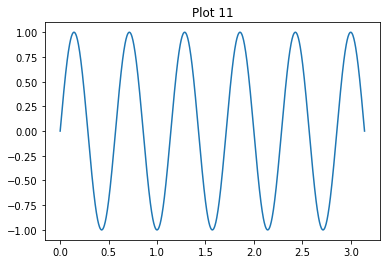

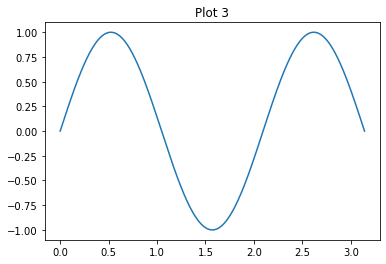

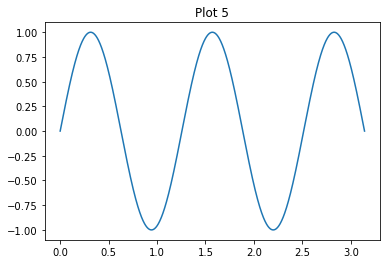

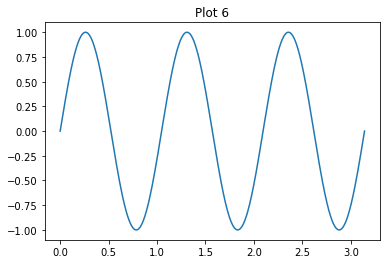

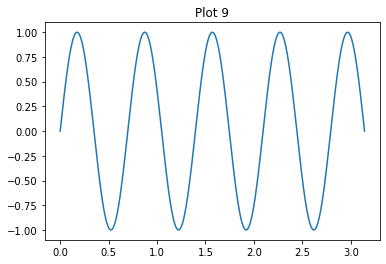

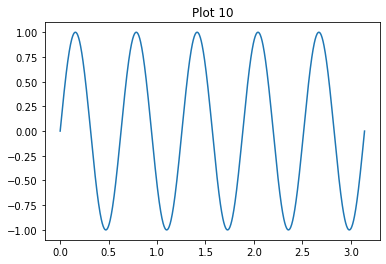

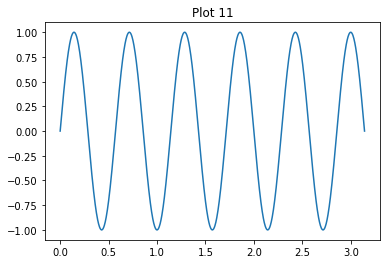

[16]:

%%px --group-outputs=engine

x = np.linspace(0,np.pi,1000)

for n in range(id+1,12, stride):

print(n)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(x,np.sin(n*x))

plt.title("Plot %i" % n)

[stdout:0]

1

5

9

[stdout:3]

4

8

[stdout:1]

2

6

10

[stdout:2]

3

7

11

[output:3]

[output:3]

[output:0]

[output:2]

[output:1]

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

When you specify ‘order’, then individual display outputs (e.g. plots) will be interleaved.

%pxresult takes the same output-ordering arguments as %%px, so you can view the previous result in a variety of different ways with a few sequential calls to %pxresult:

[17]:

%pxresult --group-outputs=order

[stdout:0]

1

5

9

[stdout:1]

2

6

10

[stdout:2]

3

7

11

[stdout:3]

4

8

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

Single-engine views¶

When a DirectView has a single target, the output is a bit simpler (no prefixes on stdout/err, etc.):

[18]:

from __future__ import print_function

def generate_output():

"""function for testing output

publishes two outputs of each type, and returns something

"""

import sys,os

from IPython.display import display, HTML, Math

print("stdout")

print("stderr", file=sys.stderr)

display(HTML("<b>HTML</b>"))

print("stdout2")

print("stderr2", file=sys.stderr)

display(Math(r"\alpha=\beta"))

return os.getpid()

dv['generate_output'] = generate_output

You can also have more than one set of parallel magics registered at a time.

The View.activate() method takes a suffix argument, which is added to 'px'.

[19]:

e0 = rc[-1]

e0.block = True

e0.activate('0')

[20]:

%px0 generate_output()

[stdout:3] stdout

[stderr:3] stderr

[output:3]

[stdout:3] stdout2

[stderr:3] stderr2

[output:3]

Out[3:14]: 2558

[21]:

%px generate_output()

[stdout:2] stdout

[stderr:2] stderr

[output:2]

[stdout:2] stdout2

[stdout:1] stdout

[stderr:1] stderr

[stderr:2] stderr2

[output:2]

[output:1]

[stdout:1] stdout2

[stderr:1] stderr2

[output:1]

[stdout:0] stdout

[stdout:3] stdout

[stderr:3] stderr

[output:3]

[stdout:3] stdout2

[stderr:0] stderr

[output:0]

[stdout:0] stdout2

[stderr:3] stderr2

[stderr:0] stderr2

[output:3]

[output:0]

Out[0:14]: 2551

Out[1:14]: 2553

Out[2:14]: 2555

Out[3:15]: 2558

As mentioned above, we can redisplay those same results with various grouping:

[22]:

%pxresult --group-outputs order

[stdout:0]

stdout

stdout2

[stdout:1]

stdout

stdout2

[stdout:2]

stdout

stdout2

[stdout:3]

stdout

stdout2

[stderr:0]

stderr

stderr2

[stderr:1]

stderr

stderr2

[stderr:2]

stderr

stderr2

[stderr:3]

stderr

stderr2

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

[output:3]

[output:0]

[output:1]

[output:2]

[output:3]

Out[0:14]: 2551

Out[1:14]: 2553

Out[2:14]: 2555

Out[3:15]: 2558

[23]:

%pxresult --group-outputs engine

[stdout:0]

stdout

stdout2

[stderr:0]

stderr

stderr2

[output:0]

Out[0:14]: 2551

[stdout:1]

stdout

stdout2

[stderr:1]

stderr

stderr2

[output:1]

Out[1:14]: 2553

[stdout:2]

stdout

stdout2

[stderr:2]

stderr

stderr2

[output:2]

Out[2:14]: 2555

[stdout:3]

stdout

stdout2

[stderr:3]

stderr

stderr2

[output:3]

Out[3:15]: 2558

Parallel Exceptions¶

When you raise exceptions with the parallel exception, the CompositeError raised locally will display your remote traceback.

[24]:

%%px

from numpy.random import random

A = random((100, 100, 'invalid shape'))

[0:execute]:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/tmp/ipykernel_2551/1064401740.py in <module>

1 from numpy.random import random

----> 2 A = random((100, 100, 'invalid shape'))

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random()

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random_sample()

_common.pyx in numpy.random._common.double_fill()

TypeError: 'str' object cannot be interpreted as an integer

[1:execute]:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/tmp/ipykernel_2553/1064401740.py in <module>

1 from numpy.random import random

----> 2 A = random((100, 100, 'invalid shape'))

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random()

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random_sample()

_common.pyx in numpy.random._common.double_fill()

TypeError: 'str' object cannot be interpreted as an integer

[2:execute]:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/tmp/ipykernel_2555/1064401740.py in <module>

1 from numpy.random import random

----> 2 A = random((100, 100, 'invalid shape'))

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random()

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random_sample()

_common.pyx in numpy.random._common.double_fill()

TypeError: 'str' object cannot be interpreted as an integer

[3:execute]:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

/tmp/ipykernel_2558/1064401740.py in <module>

1 from numpy.random import random

----> 2 A = random((100, 100, 'invalid shape'))

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random()

mtrand.pyx in numpy.random.mtrand.RandomState.random_sample()

_common.pyx in numpy.random._common.double_fill()

TypeError: 'str' object cannot be interpreted as an integer

Remote Cell Magics¶

Remember, Engines are IPython too, so the cell that is run remotely by %%px can in turn use a cell magic.

[25]:

%%px

%%timeit

from numpy.random import random

from numpy.linalg import norm

A = random((100, 100))

norm(A, 2)

[stdout:1] 5.85 ms ± 108 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each)

[stdout:2] 6.01 ms ± 108 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each)

[stdout:0] 6.29 ms ± 714 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each)

[stdout:3] 6.39 ms ± 503 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each)

Local Execution¶

You can instruct %%px to also execute the cell locally. This is useful for interactive definitions, or if you want to load a data source everywhere, not just on the engines.

[26]:

%%px --local

import os

thispid = os.getpid()

print(thispid)

2497

[stdout:0] 2551

[stdout:1] 2553

[stdout:2] 2555

[stdout:3] 2558